Expanding Your Window of Tolerance for Emotional Resilience

A helpful concept for staying grounded.

By Robin Arnett, LCSW

If you’ve ever wondered “Why do I feel so overwhelmed by small things?” or “Why do I sometimes feel numb or shut down even when I want to engage?” — you’re not broken. Your nervous system is doing exactly what it was designed to do.

The concept of the Window of Tolerance, originally developed by psychiatrist Dr. Dan Siegel, offers a compassionate framework for understanding how our nervous systems respond to stress, connection, and threat. It helps us make sense of our emotional and physiological reactions — and, importantly, shows us that regulation is not about being calm all the time, but about having enough capacity to move through life with flexibility and self compassion.

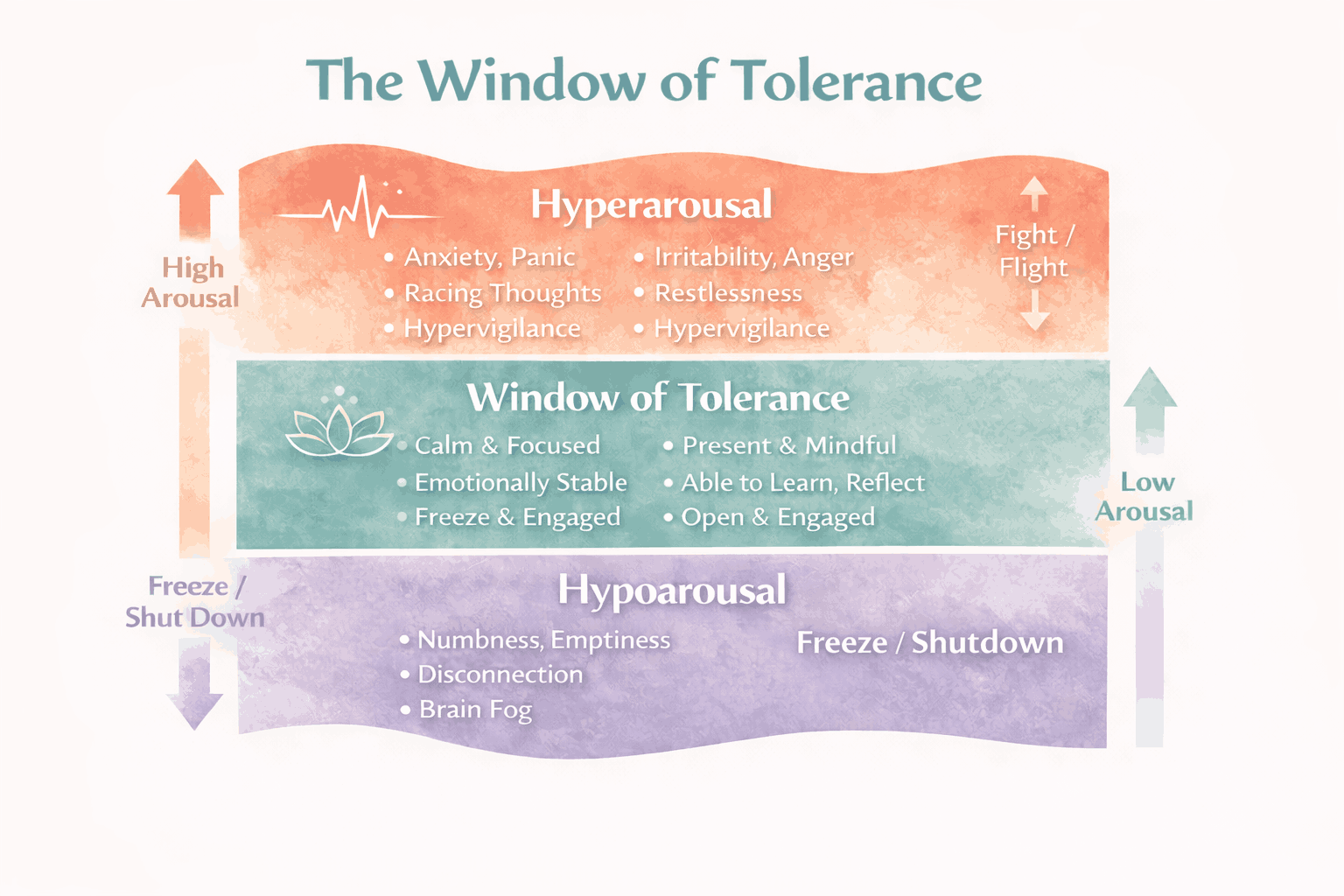

What Is the Window of Tolerance?

Your “window of tolerance” refers to the range of nervous system activation where you feel present, grounded, and able to respond rather than react. Within this window, you can think clearly, feel your emotions without being overwhelmed, and stay connected to yourself and others — even when life is challenging.

When stress, trauma, or overwhelm push you outside of this window, your nervous system shifts into survival mode. This typically happens in one of two directions:

Hyperarousal (overactivation)

Hypoarousal (underactivation)

This blog will help you to understand these different states of arousal, how to recognize where you are in the moment, how to return to your window of tolerance, and how to widen your window of tolerance over time so that you are able to tolerate more activation while staying grounded, connected, and aware.

Hyperarousal: High Alert

Hyperarousal occurs when your nervous system perceives a threat and shifts into fight-or-flight mode. This state activates the sympathetic nervous system and prepares you for action. Common experiences in a state of hyperarousal include:

Racing thoughts or difficulty concentrating

Anxiety, panic or a sense of urgency

Irritability, anger, or emotional reactivity

Restlessness or inability to relax

Tightness in the chest, jaw, or shoulders

Difficulty sleeping

Feeling “on edge” or hyper-vigilant

In this state, your body is mobilized to do something — even if there is no immediate danger. This state is a natural, adaptive response that developed to help us survive in the event of a threat. The problem is that we can be activated to hyperarousal when there is no threat present, or when the threat is psychological, emotional, and relational vs. an actual threat to life and limb. This can lead to responses that are unhelpful, inappropriate, and damaging to our relationships. Being in a state of hyperarousal is also taxing to our nervous systems. Spending too much time in this zone can lead to chronic stress, adrenal fatigue, and burnout.

Hypoarousal: Shut Down

Hypoarousal occurs when the nervous system shifts into freeze or shutdown mode. When we think of survival responses, fight and flight most often come to mind, but freeze and shutdown are just as relevant. Rather than mobilizing, the nervous system slows down to conserve energy. Hypoarousal activates the parasympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system - specifically the dorsal vagal complex.

This response often emerges when fight or flight feel impossible or unsafe. Freeze happens as a strategy to go undetected, and shutdown takes place when fighting back would be more dangerous than keeping still. This response will often be triggered if there is an adversary (animal or human) who is much bigger or more well-armed.

*A note on the freeze response: freeze can also take place in hyperarousal as a temporary state activated by the sympathetic nervous system. The freeze response in hypoarousal is more prolonged and linked to shutdown through a dorsal vagal response.*

Being in a state of hypoarousal can show up as:

Numbness or emotional flatness

Disconnection from your body or surroundings

Dissociation

Fatigue or heaviness

Brain fog or difficulty thinking

Low motivation

A sense of collapse or withdrawal

It’s important to know that we don’t have control over the way that our body responds to a threat. In that moment, our body will make an assessment of how best to respond with survival as the ultimate goal. Your body may determine that the best way to survive a threatening encounter is to submit. It is extremely common for people to feel guilt and shame around experiencing a freeze or shutdown response, wondering why they didn’t scream or fight back. It is important to know that this was not a conscious choice. This was your body protecting you in the best way it knew how.

Life Inside the Window of Tolerance

In contrast to these two states, being within your window of tolerance feels like being present, grounded, engaged, connected, clearheaded, and focused. In this state, you are energized without being tense. This is the state where learning, healing, creativity, and connection are most accessible. Importantly, being in your window does not mean feeling happy or calm all the time — it means you have sufficient internal resources to stay with your experience without becoming overwhelmed or shutting down.

Too Much Time Outside the Window

Hyper and hypoarousal are both natural and adaptive responses to threatening stimuli, and it should by no means be the goal to eliminate these states completely. At some point, any of us could confront a situation that requires that we have access to these survival strategies.

That being said, spending too much time outside of the window of tolerance is problematic in many ways. A narrowing of the window of tolerance is a common symptom of PTSD, especially complex PTSD with origins in childhood trauma. When your window of tolerance is too narrow, your perception of threat becomes skewed.

Too much time spend in hyperarousal leads to chronic anxiety, interpersonal conflict, and a constant feeling of stress that may not even have a direct cause. On the other hand, too much time spent in hypoarousal leads to missing out on life. You may find yourself drifting through your days, losing chunks of time, and having difficulty connecting with the people around you.

Spending more time within your window of tolerance requires mindfulness to help recognize where you are in the moment, and a strong set of coping tools to help bring you back to baseline.

Why Do We Move Outside of Our Window?

Moving outside of our window of tolerance can be triggered by many factors. The capacity of our window of tolerance is impacted by:

Trauma history

Nervous system sensitivity

Current stressors

Sleep, nutrition, and physical health

Relationship safety and support systems

Self-compassion and awareness

With or without the presence of a physical threat, we can be pushed outside of our window by interpersonal conflict, sensory overload, and overwhelming day-to-day stressors. Even if you currently live within a limited window, know that it is possible to grow, change, and heal by widening that window.

Spending More Time Within the Window of Tolerance

Expanding your window of tolerance is part of a comprehensive approach to healing. In fact, your capacity to tolerate distress is important in any kind of therapeutic work, because healing requires that you be able to stay with discomfort and confront difficult material. Therefore, working with the window of tolerance is an essential part of any therapeutic modality.

Titration and Pendulation

One important way to build up your window of tolerance is through intentional practice sitting with intense emotions. You can do this through titration, which means monitoring the intensity of a feeling so that it remains tolerable, and pendulation, which means spending some time with an uncomfortable feeling before returning to a comfortable, grounded state. By intentionally building your tolerance (ideally with the support of a therapist), you can grow your capacity like a muscle, gradually expanding what you are able to handle without getting flooded.

Mindfulness

Recognizing when you are outside of your window is the first step to returning to it. This kind of awareness is difficult to develop by yourself (you don’t know what you don’t know, right?). That’s why working with a therapist can be extremely helpful in this process. A therapist can help you to recognize when you are in an activated or shut down state, and guide you in recognizing the signs that show up for you.

Improving Regulation Skills

Once you’ve become aware that you are outside of your window, it’s time to utilize a coping strategy to either calm down if you’re hyperaroused, or reengage if you are hypoaroused. There are a multitude of ways to ground and return to awareness, but some of my favorites are 5, 4, 3, 2, 1, EFT tapping, and any kind of intentional movement.

Supportive Relationships

Healing happens in connection. Supportive relationships help to support the nervous system through coregulation. You don’t have to go through it alone. Therapists, support groups, and friends and family are all essential relational resources as you approach your healing journey.

A Final Note

Your nervous system has been shaped by your experiences — and it has been doing its best to protect you. Learning about the window of tolerance isn’t about fixing yourself; it’s about befriending your body and building capacity with care.

With patience, support, and intentional practice, it is possible to experience more moments of presence, connection, and ease — even when life is hard. If you’d like support expanding your window of tolerance, working with trauma-informed therapy can be a powerful place to begin. Healing is possible, and it begins with a single step.